Growing up, many Australians have understood and taken ‘Australia Day’ to be a natural and inevitable part of the Australian story, choosing not to view it through a critical lens. Fireworks are held, barbecues with friends and family are enjoyed, days off from work or school are gratefully accepted. Some choose to celebrate the notion of contemporary Australia as a multicultural, peaceful, united place in which everyone is given a ‘fair go’ – this idea of Australia as the ‘lucky country’ is deep rooted and pervasive in the collective Australian psyche.

But taking a critical view asks of us that we engage more deeply with these concepts – the lucky country… for whom? A fair go… for whom? And what exactly is this notion of the ‘nation’ that we accept as not only inevitable but worthy of a collective celebration?

Historian and researcher Samantha Owen, from Perth’s Curtin University, says national days serve to remind people of their “sense of belonging to the idea of a nation and what it represents”. For national days to be successful, they require consensus among citizens that the date chosen, and the ‘idea’ of the nation, are indeed worthy of celebration.

The idea of the nation

The idea of the ‘nation’ or nation-state is crucial to understanding not only ‘Australia Day’, but all national holidays. While nations seem obvious and natural, they were (at least in their current form) in fact a modern European colonial phenomenon developed in order for a large population to fund warfare and to be organised into a centralised state with a single government, power structure and economic system. Nations are, in other words, socially constructed.

According to political scientist Benedict Anderson, nations are “imagined communities” of people who believe themselves to be part of some larger identity. Anderson says, a nation…

…is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.

In other words, nations are social constructs – ideas that become and stay ‘real’ by the imaginations of the groups of people who believe in them. The nation is not only a place, it is a political community. And defining what this community we call the nation is means that we have to understand what it is not.

Feminist scholar Sara Ahmed explains that nations work not just by gathering differing individuals together in a common sense of belonging and inclusion, but by defining who is excluded and out of place. Just like nations have physical borders which determine the boundaries of who belongs and does not belong, they also have figurative and emotional definitions of who can be included in the identity of the nation.

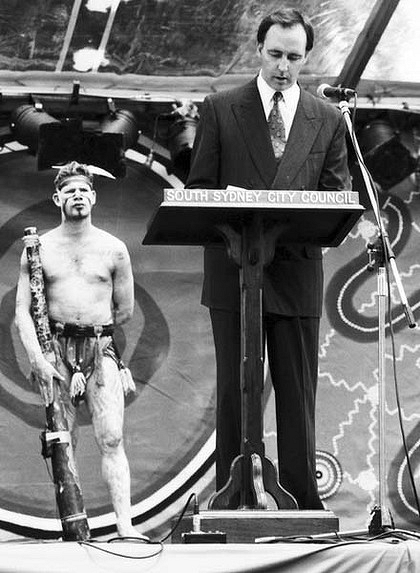

Similarly, Dominic O’Sullivan, a professor in comparative Indigenous politics and public policy at Charles Sturt University, says that national days – whether days of celebration or of contest – raise the question ‘what do we mean by a nation?’ And who is the ‘we’ who makes up this nation?

This question about who belongs in and to the nation is particularly relevant when understanding settler colonial nations like Australia, which were formed by creating a contrast between the settler (white, ‘civilised’, modern, insider) and the ‘native’ (dark, traditional, threatening, outsider).

‘Australia’ became a nation on 1 January 1901. But what about the 60,000 years of belonging – to Country, to stories, to culture and language and lore – before that?

National days

In their book National Days, scholars David McCrone and Gayle McPherson argue that national days are ‘commemorative devices’ for reinforcing national identity. They ask:

“What could capture better the essence of being a ‘national’ than setting aside a holiday on which to celebrate who we are, and how we got here, selecting a day to mark out calendrically what it means to be a member of a national community?”

In this sense, national days are important signifiers of national identities and function together with or alongside other national symbols – flags, anthems, currency – to signify a community underpinned by themes of ‘oneness’ or unity. As Gabriella Elgenius argues, national days are usually officially recognized events that celebrate founding myths. As such, they are socio-political events that, while they might appear consensual, are often outcomes of long periods of struggle and conflict between various groups.

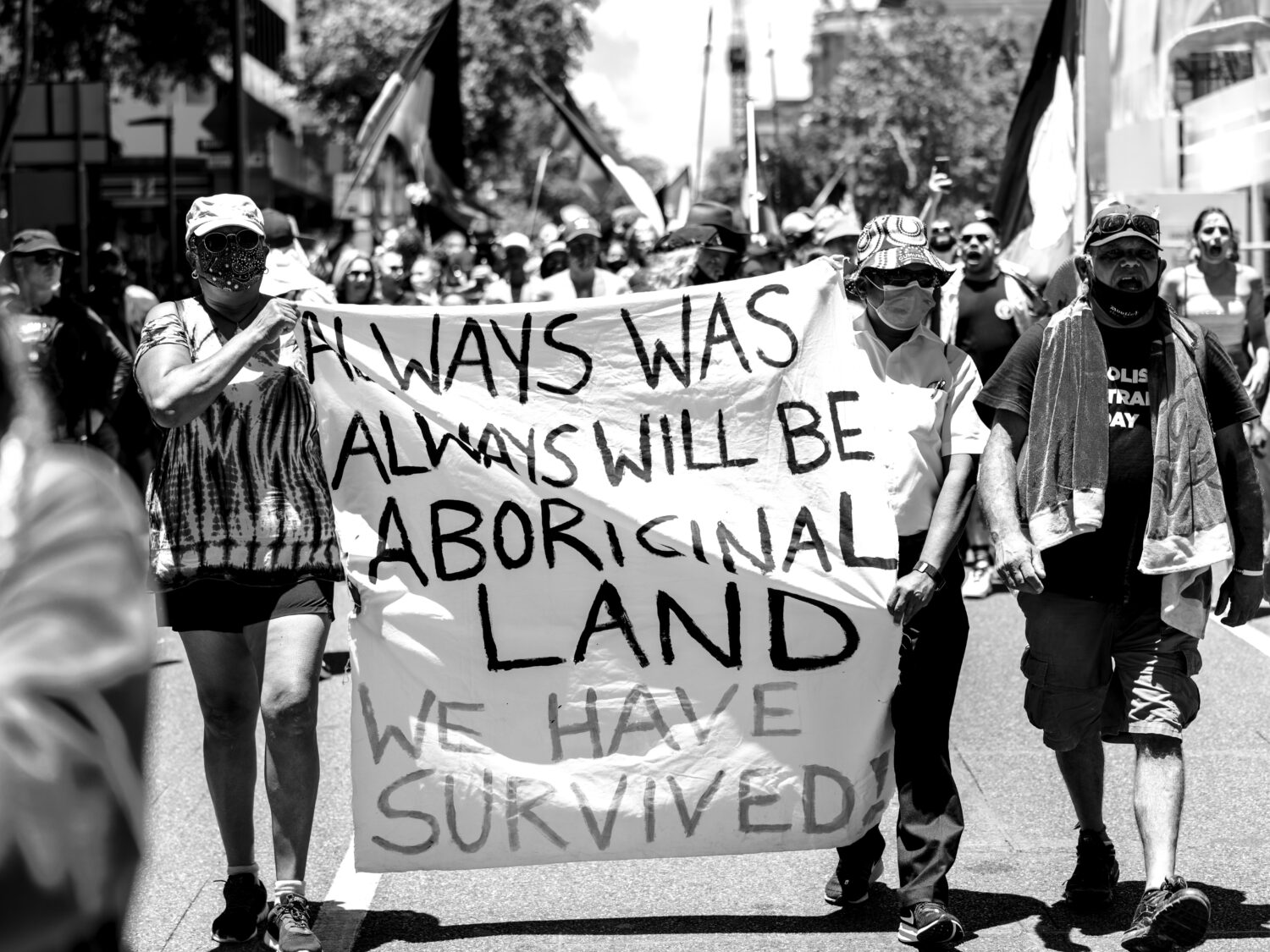

National days, in other words, can be contested, argued over, claimed and disclaimed, and reinvented. As McCrone and McPherson state, what is not celebrated is as interesting as what is. National days can be as much a process of forgetting as remembering. They are, after all, inventions of our collective making.

Memory and forgetting

This begs an interesting question: in choosing a day to celebrate Australian nationhood, what are we remembering and what are we forgetting? When we talk about national unity, who is being included and who is being excluded?

Anderson and many others have written about the role of national memory and forgetting in creating and sustaining the idea of the nation.

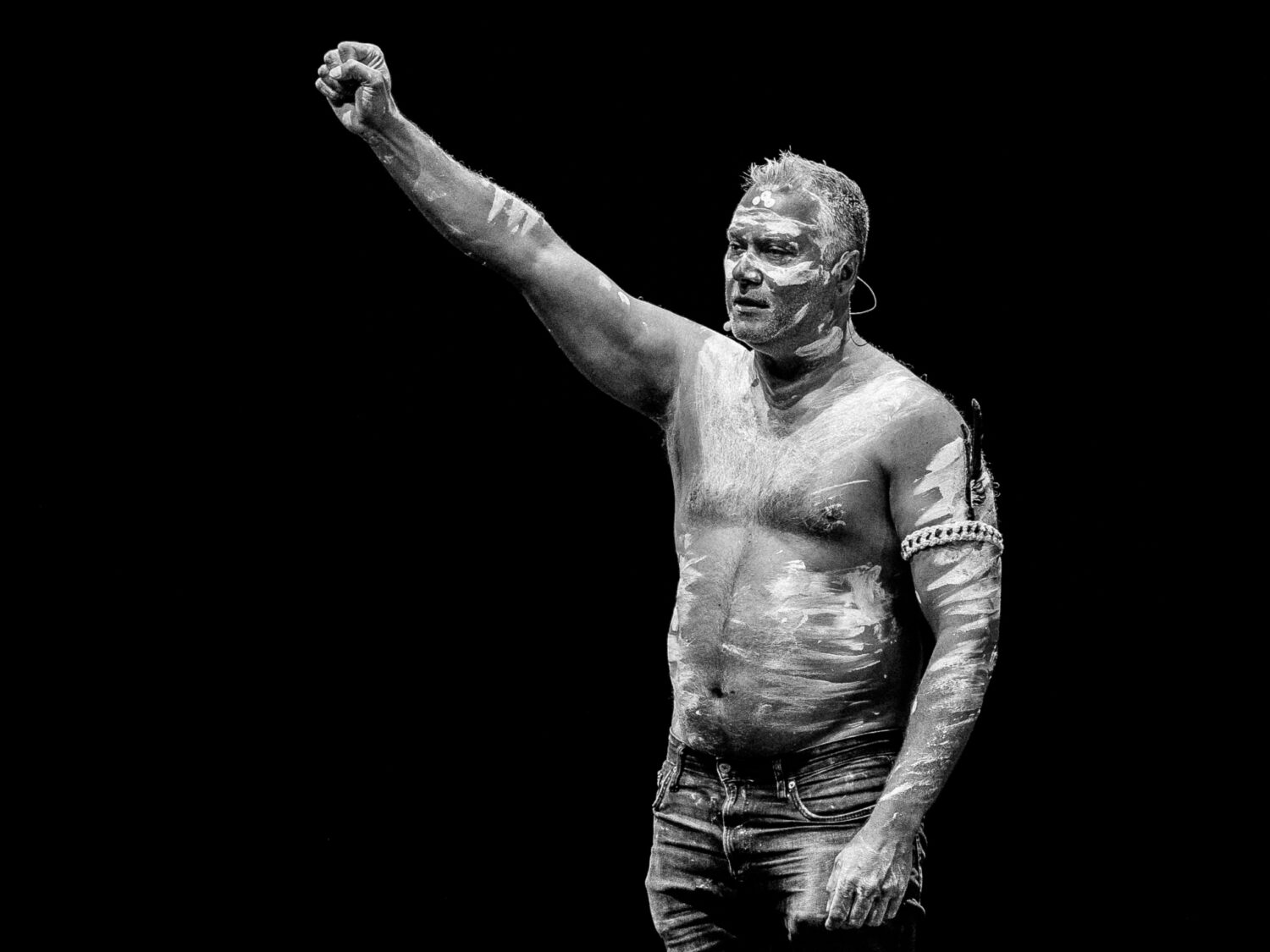

When children learn the colonial history of Australia in school, or the words of the national anthem, or when tourists visit colonial monuments and museums, they are not just engaging in the national memory – they are also being asked to participate in a collective act of forgetting. Forgetting 60,000 years of custodianship and culture, forgetting the colonial violence of dispossession and removal that ‘created’ Australia, and forgetting the resistance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who are still here, who have survived the creation of the nation that aimed to eliminate them.

Anthropologist W.E.H Stanner talked about this in his Boyer lecture of 1968 as the “cult of forgetfulness” on a national scale, where Australians are asked not only to not acknowledge the horrors of our national founding, but to forget that they ever happened. Stanner called this ‘the Great Australian Silence’. He wrote:

It is a structural matter, a view from a window which has been carefully placed to exclude a whole quadrant of the landscape. What may well have begun as a simple forgetting of other possible views turned under habit and over time into something like a cult of forgetfulness practised on a national scale.

Similarly, Gumbainggir activist and academic Gary Foley writes:

Today that same phenomenon of a cult of national amnesia persists… The problem of forgetfulness as identified by Stanner in 1968 is still out there, and since then a whole generation of Anglo-Australians has grown to maturity blissfully ignorant of the real problems confronting Aboriginal people. Further, the national ‘forgetfulness’ that Stanner observed has been compounded by torrents of misinformation, peddled initially by Pauline Hanson’s One Nation, then followed by decades of history and culture wars.

The many community and more recently State-led truth-telling activities across Australia ask us now to tell a different story, and to remember differently. What is the true history of this country? What are the languages, places, stories and sovereignties that defined this place over 60,000 years, and what role do they have in this place we now call Australia?