If asked when the concept of ‘Treaty’ entered the political lexicon in the long, long story towards reconciliation in Australia, some would say it emerged during the 1970’s-1980’s. They may also be aware that amongst most western colonising states, Australia has the dubious distinction of being the only nation that has failed to enter into any kind of agreement or Treaty with its First Nations Peoples. And this despite the fact that international and national laws of that era made provision for such agreements with local Indigenous peoples.

The date of the following quote may be a surprise to many (read on to find out):

The lack of a treaty…[was]… a fatal error…Had [the natives] received some compensation on the territory they surrendered … His Majesty’s Government would have acquired a valuable possession without the injurious consequences which have followed our occupation and which must ever remain a stain upon the colonisation of Van Diemen’s Land.

These words are taken from official dispatches between the secretary of state and colonies in London – in this case George Arthur, Governor of Van Dieman’s Land. They refer to perhaps the darkest decade in European – Aboriginal relations of nineteenth century Australia, the time of the Black War in Van Dieman’s Land. They also mark one of the earliest public acknowledgements and deep misgivings on the part of colonial authorities about the legality of the way in which European settlement was proceeding, without regard to the peoples already occupying the lands. The date is 1832!

It is understood that George Arthur’s searing experience of trying to manage the brutalities of the Black War period later prompted him to attempt to influence the setting up of the new West Australia colony and also the British authorities in negotiating a treaty with settlers and Maori peoples in New Zealand.

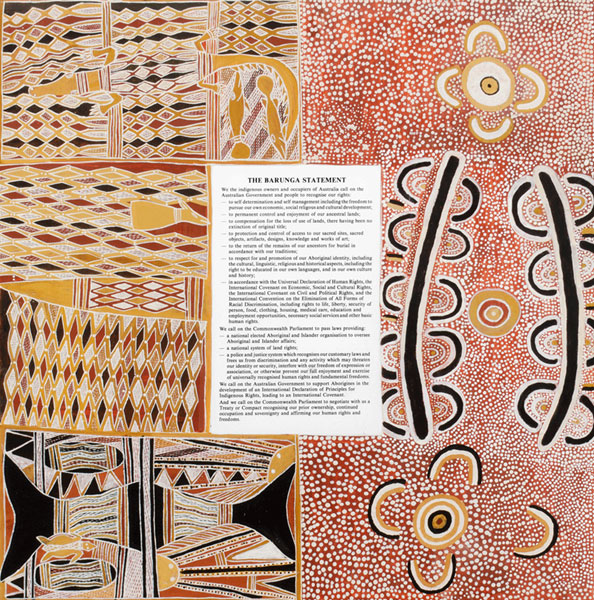

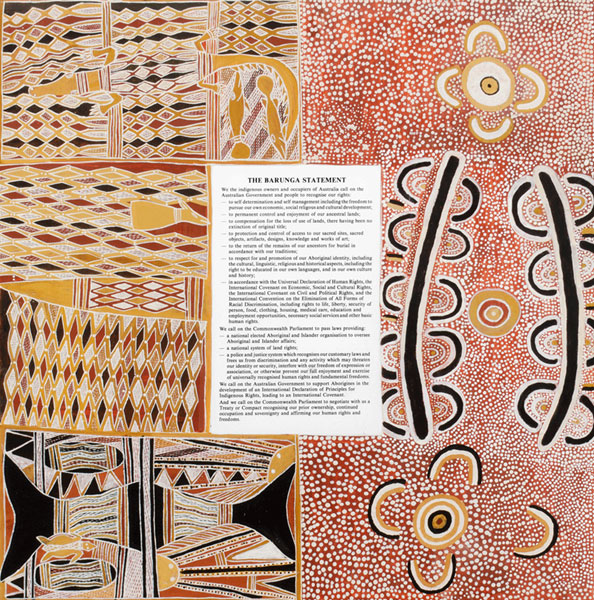

- The Barunga Statement – natural pigments on composition board with attached printed text on paper presented by the Central Land Council and Northern Land Council in 1988 to former Prime Minister Bob Hawke. Gifts collection, Parliament House Art Collection.

Bolstered by the western scientific economic rationalist world view that the colonists brought with them, the exploitation of the Australian continent proceeded apace for the next 150 years – as did the demise of its First Nations Peoples. This time has been described as:

A period of dispossession, physical ill-treatment, social disruption, population decline, economic exploitation, codified discrimination, and cultural devastation. The notional citizenship ascribed to the Aboriginal people at the beginning of this period was all but gone by the end of it.

So great was the decimation of First Nations around the country that by the late nineteenth century colonial authorities began to speak of ‘soothing the pillow of a dying race’. And as each new generation of settlers arrived, firsthand experience of the cruelties and devastation of conquest faded in settlers’ memories – a phenomenon that became known as The Great Australian Silence. Throughout this time there were white settler humanitarians who fought for justice and citizen rights for First Nations communities. However to this day the Australian Constitution of the newly formed nation in 1901 makes no mention of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Talk of treaty, compensation or other forms of reparation on the part of authorities disappeared from public discourse.

There was a renewed flourishing of advocacy for Treaty undertaken by non-Indigenous Australians from the late 1970’s onwards. High profile Australians such as economist and public servant Nugget Coombs and poet Judith Wright were driving forces in the formation of the Aboriginal Treaty Committee (1979-83) whose aim was to promote treaty amongst non-Indigenous Australians.

In fact throughout the entire nineteenth and twentieth centuries and right up to the present time, First Nations Peoples have been actively engaged in their struggle for basic human rights, despite the disadvantage of their socio-economic status.

These efforts are recorded in a remarkable publication – The Struggle for Aboriginal Rights by Bain Attwood and Andrew Markus – a documentary history of Indigenous initiated actions ‘fighting to be granted or to retain reserve lands, battling to govern themselves, or to be treated fairly by settler authorities’. Even more surprising is the number of times the word ‘Treaty’ appears in an index search of these advocacy /petition writings. Sixteen separate entries use the word in negotiations with authorities. The earliest of these was in the 1830’s in Van Dieman’s Land and among the latest, the more well known Barunga Statement (1988), and the early documents Eddie Koiki Mabo submitted for his case. The Mabo case, begun in the early 1980’s, finally upended the myth of terra nullius in the Mabo Native title win of 1992.

In 2017, the Uluru Statement from the Heart called for a Makarrata Commission to oversee treaty making at local and national levels as part of a package of reforms that together became known as Voice, Treaty and Truth. The statement together with the campaign that followed, led and echoed by many First Nations activists echoing this call, acted as a catalyst for treaty once again gaining prominence in the national discourse. Read more about how treaty is progressing in the states and territories here.